Book review of “Hacking Darwin” by Jamie Metzl

by Jamie Metzl

2020, 269 pgs, 309 pgs including footnotes.

This book is an exploration of how we might genetically engineer our children, why we might want to do so, and what the consequences might be. The fact is, some people are already “hacking Darwin”. The first “test-tube baby” was born in 1978. This set the stage for preimplantation genetic testing, which became popular in the 1990s and widely used today. But “hacking Darwin” had already been occurring earlier due to genetic testing. A striking example Metzl discusses is the rapid decrease in Tay-Sachs disease in the Ashkenazi jewish community. Tay-Sachs is a genetic disorder which has devastating effects on the nervous system. By age 2, children with Tay-Sachs start to experience seizures and decline in mental functioning. Sadly, most die in agonizing pain by the age of five. About one in twenty seven Ashkenazi Jews carry the Tay-Sachs genes. Remarkably though, since the 1980s, the prevalence of the disease among Ashkenazi Jews has been very low, due to extensive genetic testing and family planning. Marriages between people who have tested positive for the disease were discouraged, and when they do occur, the couples tended to adopt rather than risk having a child born with the disease. The result was a great reduction in needless suffering, which is hard to argue against.

One of the major objections to genetic engineering is that it is “unnatural”. Metzl points out that a better term is “unfamiliar”. He points out that many things that seem natural are actually very “unnatural” – for instance, if you went back a few thousand years, you wouldn’t find anything resembling today’s corn or bananas – they are human concoctions from centuries of selective breeding. It seems that the queeziness people feel, which they label as due to “un-naturalness” is actually just due to unfamiliarity, which naturally invokes anxiety. History shows us that any radical technology or new idea naturally experiences widespread pushback. But history also shows that acceptance of a radical new idea or technology can be remarkably fast notwithstanding.

In-vitro fertilization provides an interesting case study of how public opinion can shift. Initially it was demonized, but public acceptance of it rapidly changed over the course of only a few years.

The next technology that will come down the pipeline, according to Metzl, is iterated embryo selection. Embryos are already inspected visually to select the one that is least likely to result in a miscarriage, and as noted in some cases preimplantation genetic testing is performed to check for a few genetic illnesses. This process can be scaled up and improved dramatically. Instead of having 10-15 eggs fertilized, a hundred might be, and instead of just doing visual checks, the genome of each embryo might be sequenced to screen out certain genetic disorders and select for certain traits. The process could also be “iterated”, using induced pluripotent stem cells (IPCs) from the embryos to create new gametes (eggs & sperm) which could be combined to create new embryos.

The benefits of expanding IVF and embryo selection could not only eliminate unnecessary suffering but also result in large financial savings which will allow money to be redistributed elsewhere in our healthcare system. The current cost of taking care of the current number of people born with genetic diseases each year was roughly estimated by Metzl to be $48 billion, spread over 37 years into the future.

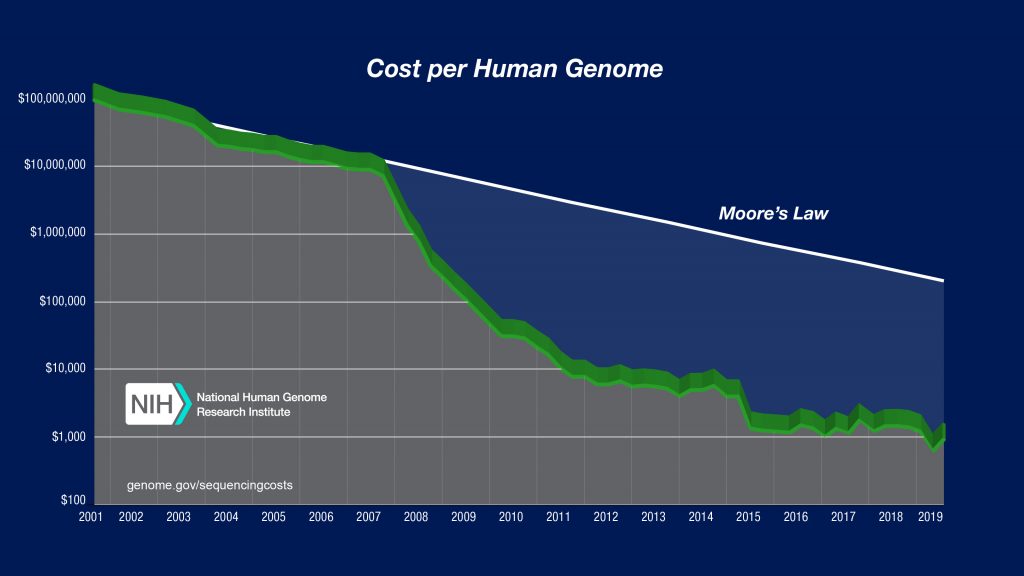

The cost of sequencing is dropping dramatically (see Fig. 1). This is allowing for larger genome-wide association studies (GWASs). Using big data, statistical methods, and machine learning, many outcomes can be predicted by analyzing the many genes which can influence most traits. Already, the height a child will grow to can be predicted to within an inch (assuming they get adequate nutrition) by analyzing thousands of genes.

Two major types of enhancements which will benefit our offspring are discussed in length by Metzl – increased intelligence and increased healthspan, and it’s worth discussing some of his main findings here. (Other possible enhancements he notes are increased empathy, supersensory capabilities, increased physical stamina and strength, increased beauty, increased ability to extract nutrition from foods, and better ability to tolerate mircrogravity and radiation.)

Regarding intelligence, the Minnesota Family Twin study found that 70% of IQ is genetic. More recent works put the number somewhat lower (about 50%), but a surprising amount is hereditary, and the variance due to genetics is significant (about 15 points of IQ in each direction). The rest seems to be largely due to things like childhood nutrition and having a rich environment as a kid. Higher IQ provides many benefits. Among them is a better ability to adapt to change and work in a dynamic environment where you constantly have to learn new skills. Statistically, people with lower IQ tend to work jobs with a regular routine, such as service positions. Currently, those with low IQ can still have a great life (there’s not much evidence IQ correlates with happiness), and low-IQ people can learn a trade where there is reliable demand, become very good at it, and be valued by society. With the advent of AI and robotics, this is rapidly changing, and the risk of large-scale technological unemployment is real. Metzl asks, in light of this, is it really fair that we are trusting the economic wellbeing of our children to the genetic lottery of sexual recombination? It’s already not easy to compensate for a bad draw in the genetic lottery. Additionally, if other parents are doing it, why would any parent want to risk their child being far behind their peers? According to Metzl, the choice will be clear for parents in the future.

The second major area where genetic engineering will have an effect is aging. The diseases of aging were not something evolution cared much about, so there are likely genetic hacks that are possible but were just never selected for – it’s an area ripe for optimization. For a glimpse of what is possible, Metzl has us consider the naked mole rat, a species which is remarkable in many ways (click here for a full list of ways this species is special). Most notably, naked mole rats don’t exhibit the normal signs of aging, and they don’t get cancer. Thus, as odd as it may seem, the naked mole rat is the subject of intense research, and this humble species even serves as a sort of touchstone increasing the confidence of venture capitalists investing in longevity biotech startups in Silicon Valley. According to Metzl, “Calico, Google’s San Francisco–based life-extension company, maintains one of the world’s largest captive colonies of naked mole rats to see if it can uncover biomarkers of aging and unlock the secrets of naked mole rat longevity.”

It seems that genetic engineering will eventually be accepted as the ethically superior way of creating children – no one will want to leave something as important as the health and economic wellbeing of their children to blind chance. Human beings naturally crave control and certainty where possible — that’s why we give our kids vaccines and parents spend thousands of dollars on prophylactic dental procedures such as orthodontics or the removal of wisdom teeth. Yes, there will always be some hold-outs who will want to stick with “traditional conception”, but after reading Metzl’s book I can’t help but think that eventually the numbers will be quite small. Consider, for instance, that even the Amish use modern medicine.

The scientific and technological path to a much more healthy world, with much less suffering and longer, healthier lives is clear. There are straightforward steps we can take to reduce congenital ailments, for instance. However, there’s a real chance we may delay even this for decades, causing much needless suffering. Part of the reason is that any discussions of the subject immediately bring up a lot of cultural baggage from the horrible legacy of eugenics. The horrors of eugenics form an unfortunate negative emotional halo around any discussion of genetic engineering. While the eugenics movement is largely dead, the subject is so important that Metzl rightly devotes a large part of the book to it. Concerns about a re-emergence of the horrors of eugenics are legitimate, but conflation of what is being proposed with those horrors is not. Eugenicists advocated forced sterilization, whereas nobody is proposing that today. Instead, all that is being proposed is that parents have a choice in how their children are conceived. However, there is a real concern that parents will voluntarily choose children with certain biases, such lighter skin and heterosexuality. There are also concerns that the creation of genetically engineered “super children” would lead to a caste system of some sort, leading to a highly in-equitable society where the non-genetically-engineered are constantly discriminated against and made to feel unworthy. Metzl acknowledges each of these risks as real, but he also points out that none of the scenarios are inevitable and asks the reader to consider the benefits of genetic engineering as well, some of which we previously discussed. He notes that our current world is already very unequal in terms of genetics. Might a bit more genetic inequality be acceptable, Metzl asks, if the children created make enormous contributions to the arts and sciences which benefit all of humanity? Regarding whether a caste system might form, Metzl suggests that we must work to ensure the technology is widely distributed (at one point I recall he suggests insurance companies might have an incentive to provide genetic engineering as it would reduce health costs later on). A bigger horror, Metzl suggests, is not genetic inequality, but perfect genetic equality – the creation of a uniform generation of cookie-cutter children, where misfits and non-neurotypical people (which have historically contributed so much) have been selected out. Each of these concerns are real, and Metzl doesn’t try to argue otherwise. Metzl does a good job of laying out the terrain of possible benefits and problems in a very open-eyes, unbiased way, providing information to the reader and letting them make their own judgment.

While ethical concerns may slow the development of genetic engineering, there’s also the distinct possibility of a genetic arms race, which would speed things up. In other areas such as AI, China is making more aggressive investments in genetic technology – a “$9 billion, fifteen-year investment to improve national leadership in precision medicine”. Metzl points out that the Chinese seem to have far fewer hang-ups around the subject and are blazing full steam ahead.

While the author is sympathetic to genetic engineering, the book presents a balanced treatment and never waxes too polemical. The first part of the book is mostly about the science. The later sections, on the ethical concerns and the genetic arms race scenario, are the most thought-provoking and are parts I may re-listen to at some point. Overall, this book is a very timely and thought-provoking introduction to the subject.

Note: as a happy coincidence, David Wood of the London Futurists recently had Metzl speak to his group, and you can watch a recording of the event here.