Moore's law – Kurzweil vs. Thiel

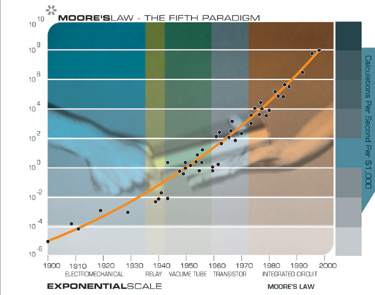

Everyone knows what Moore’s law is – processors become cheaper, exponentially. There are a multitude of more precise formulations. Moore’s original formulation was very precise – it stated that the density of transistors achievable with the lowest cost transistor doubles every two years. A few years later he revised the doubling time to every 18 months. Personally, I prefer Ray Kurzweil’s formulation – the computational power (measured in calculations per second) available for $1000 doubles every ~2 years. The two versions are nearly identical, but using calculations per second per $1000 also takes into account how well the transistors are used (layout) and driven (clockspeed).

Most place the start of Moore’s law in the year 1965, when he published his paper on the subject, or a few years prior, in 1959, when the planar silicon transistor was invented. Kurzweil’s approach, using calculations per second, allows one to go back further, before the invention of the transistor, to 1900, when the first electromechanical calculators appeared.

Moore’’’s law is special

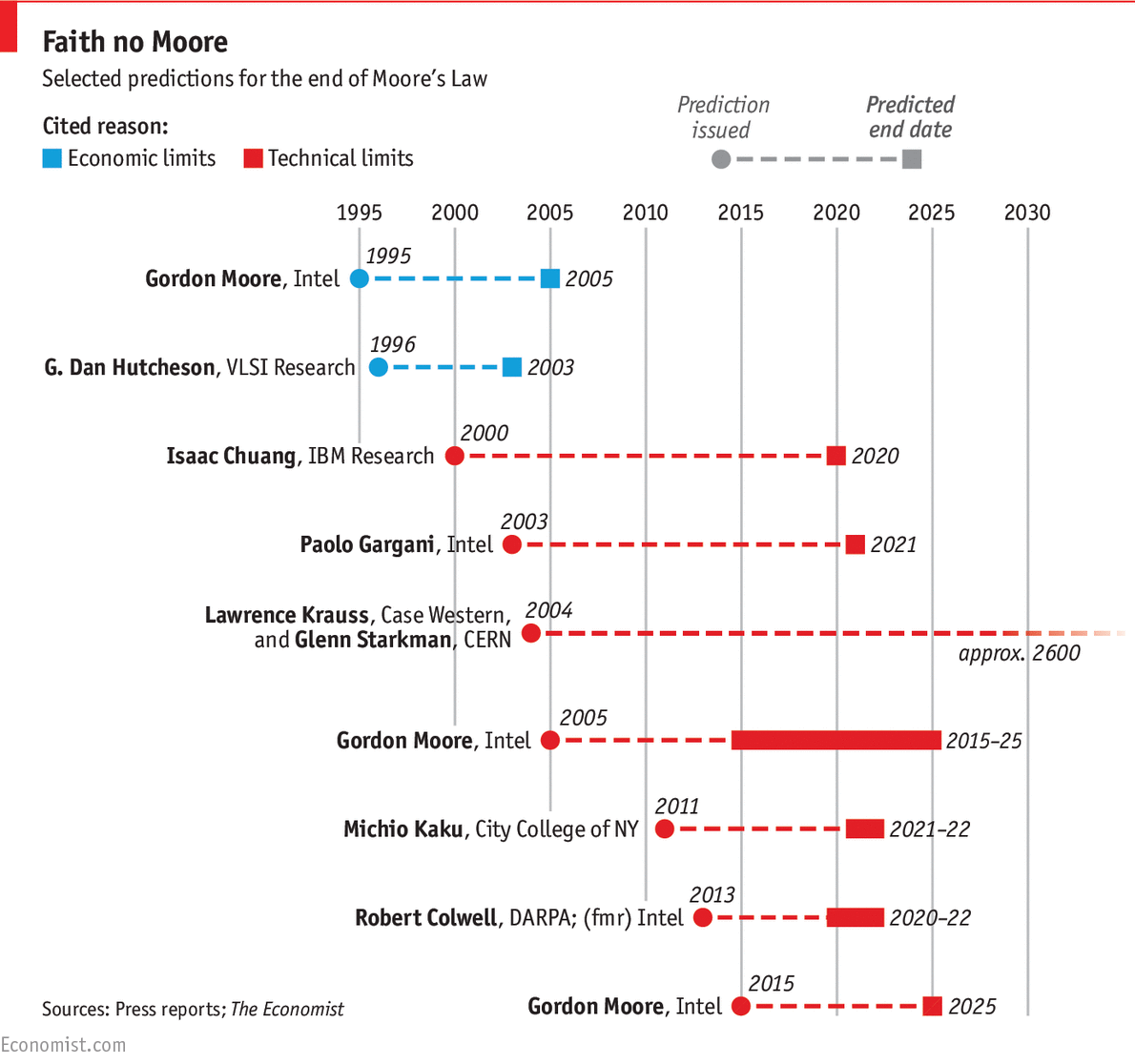

Most technological developments follow a “sideways S” shaped curve – they start flat, grow exponentially for a time, and then level off when some natural barrier is reached. There is a long history of people prematurely predicting the end of Moore’s law, or in other words, predicting when the curve will finally become a sideways S. For fun, I searched through Google’s archives for articles declaring that the end of Moore’s law was right around the corner:

2000 The End of Moore’s Law?” – MIT Technology Review – “there are good reasons to think that the party may be ending.”

2007 – “Moore Sees ‘Moore’s Law’ Dead in a Decade“ – _ExtremeTech

2009 – “Moore’s Law limit hit by 2014?” – CNET

2009 – “Researcher says Moore’s Law at end” – CNET

2010 “Life After Moore’s Law” – _Forbes

2011 – “Death of Moore’s Law Will Cause Economic Crisis” – _PCWorld

2012 – “Collapse of Moore’s Law ‘in about 10 years’” – _SlashGear__

2012 – “Physicist: Moore’s Law as we know it is on its last legs” – Network World

2013– “Silicon daddy: Moore’s Law about to be repealed, but don’t blame physics” – The Register

The Economist made a nice graphic of some of the more recent predictions:

Because it has persisted for so long, it is a widely held that Moore’s law is special. Even in the early days of Moore’s Law, the rapid improvements in transistor technology were noticed by many technologists. Douglas C. Engelbart, who would later be credited with inventing the mouse, wrote a paper discussing the trend in 1959, and gave talks on the subject, at least one of which Moore himself attended. The regularity of Moore’s law growth is also suprising. Many technological metrics show unpredictable jumps as new technological inventions “disrupt” the old.

G.D Hutchinson uses the automotive industry as an example of typical “S” curve growth. The automotive industry saw Moore’s law-like cost reductions between 1904 – 1915, when the price of cars dropped rapidly due to innovations in manufacturing. Ford’s development of the assembly line caused a reduction in price from $20,000 to $1000 (in ~1900 dollars) and then from 1000 to 300 dollars. However, pushing costs below $250 proved difficult. Even today, with highly automated assembly lines, car manufacturers haven’t been able to reduce costs. Moore’s law has covered many more orders of magnitude. As The Econonomist points out, “Were a car that uses 15 litres of petrol per 100km and costs $15,000 to improve its performance in similar fashion (to Moore’s law), it would consume less than two tenths of a millilitre of petrol per 100km and cost a quarter.”

Kurzweil’s techno-optimism

Futurist Ray Kurzweil likes to talk about the exponential or double exponential progression of technology towards the coming technological singularity. He has plotted exponential or double exponential progressions in something like 30 industries, some of which can be seen in his article “The Law of Accelerating Returns”. In my view, most of these exponentials are descendants of Moore’s law – they can be linked to the exponential reduction in cost of computer power made possible by shrinking transistor size.

To the degree to which the technologies can be linked to improvements in IT, they show a smooth exponential progression. For instance, the growth of the internet and reduction in cost of RAM are directly linked to IT, while something like “brain scanning throughput” is only partially linked. Consequently, the growth in the size of the internet follows a smooth exponential curve, while the improvement in brain scanning tech, while improving many orders of magnitude in the past decades, does so in a more sporadic fashion. DNA sequencing technology, as measured by cost per sequencing the human genome vs time, does seem to be improving robustly in an exponential manner, without much link to Moore’s law. However, many of the technologies Kurzweil labels as “exponential” have only been around a decade and may be just undergoing a temporary burst of growth. Like the cost of automobiles, these curves may level out in the next few years in the familiar sideways “S” curve. In his TED talk, Kurzweil labeled 3D printing resolution as following an exponential curve towards smaller size, and from this, concludes that nanotech will be available in the next decade, since that curve can be extrapolated down to the size of atoms. I find this very dubious. Most dubious to me is Kurzweil’s statement that “The expanding human life span is another one of those exponential trends”. Kurzweil’s plot of human lifespan vs time is not a log plot, and therefore is misleading! I will return to this problem in a bit.

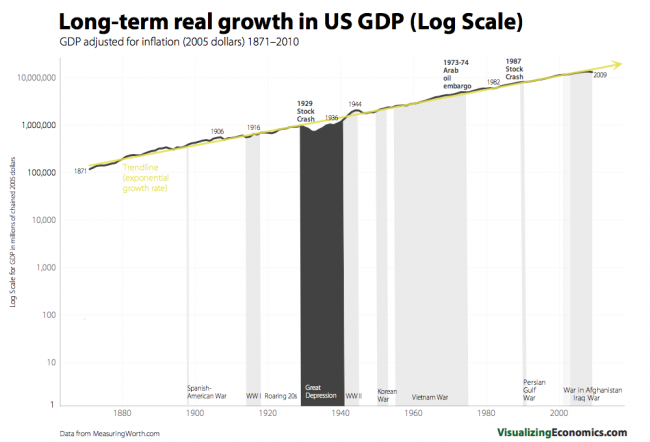

Kurzweil also points out that there is exponential growth in the economy as a whole. The overall size of the US economy has chugged along at about 3-4% growth a year for the past century:

In today’s world, “developed” (industrialized) countries grow at about 2-4%, and “developing” (industrializing) countries grow at 4-8%. Incidentally, the total energy output of the US economy also grows at a steady rate of about 3% per year. The population growth rate of the US, for reference, is about .7%. Note that all of these exponential trends have much smaller growth rates than Moores law.

Thiel’s techno-pessimism

I think the prognostications of another techno-futurist, Peter Thiel, are very contra Kurzweil. Thiel proposes that, except for information technology (Moore’s law-based technology), technological progress has slowed down or stalled. This view makes Thiel a contrarian, since the prevalent view is that we live in an era of technological progress. Thiel laid out his position in a highly cited 2011 article, “The End of the Future“. According to Thiel:

“Men reached the moon in July 1969, and Woodstock began three weeks later. With the benefit of hindsight, we can see that this was when the hippies took over the country, and when the true cultural war over Progress was lost.”

His politics aside, the basic point that Thiel makes seems to be valid. When gauging “progress” we are easily blinded by the amazing technologies made possible by Moore’s law – personal computers, the internet, and smart phones. Because of this we neglect to realize that in most other areas, we are still using the same technology we had in 1969. In other words, developments in the world of ‘bits’ blinds us to a lack of development in the world of ‘atoms’. The moon is still the furthest people have ever ventured. Cars still use internal combustion engines and airplanes still travel at top speeds of a few hundred miles per hour. Our primary sources of energy are still coal, oil, and gas. Our kitchen appliances are largely the same as they were in 1969. The future that mankind dreamed of in 1969 has largely not come to pass. We do not have talking computers, meal pills, cheap solar energy, personal robotic companions, flying cars, moon bases, supersonic airliners, space planes, space elevators, fusion energy, antimatter drives, or vacuum tube transport. Instead, we have the internet, smartphones, Facebook, Snapchat, and Twitter. In the words of Thiel:

“We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters.”

Eroom’s law

As I mentioned, I believe the most dubious of Kurzweil’s claims is that life-expectancy is also following an exponential trend. Empirically, the plot of life expectancy vs time seems to be following the “S” curve. More generally, apart from DNA sequencing technology and a few other special cases, most of healthcare technology seems to be following linear trends. In almost all areas of healthcare, costs for different procedures and treatments is increasing, not decreasing as Kurzweil would have us expect. This is partially due to bad regulations, lack of market mechanisms, and a bloated insurance system. At the same time, the cost for the development of new drugs and procedures is increasing dramatically as well. Cancer treatments are getting better, slowly, but in the process treatments have become more and more complex, requiring complex drug cocktails and genetic tests. As people live longer, the cost to maintain people in a healthy state also increases dramatically as more and more problems of old age must be addressed.

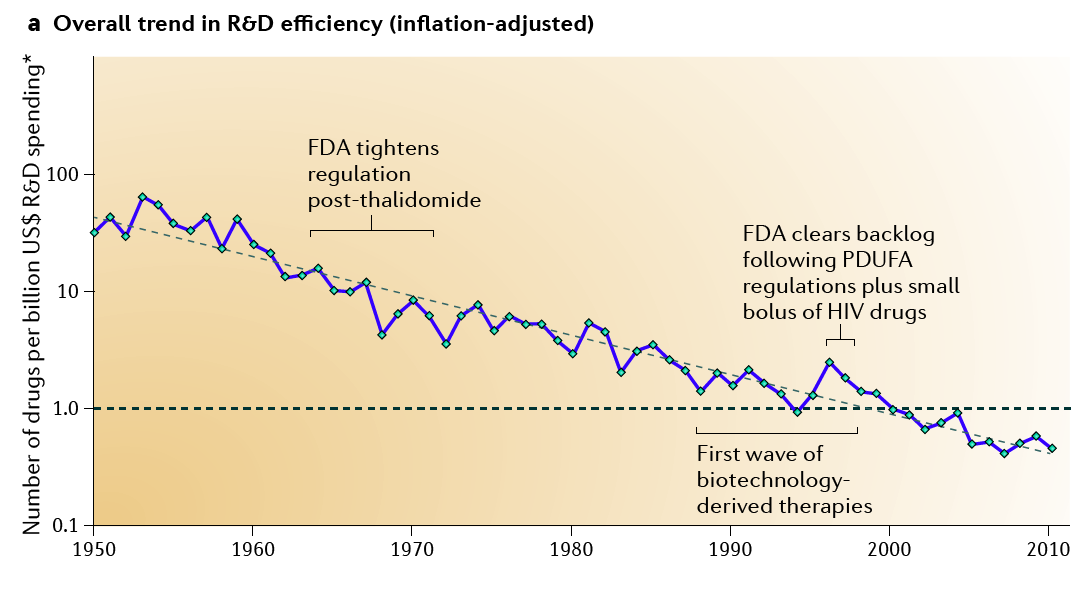

The exponentially increasing costs of drug development is codified in Errom’s law, which is Moore’s law spelled backwards:

The number of new drugs approved per billion US dollars spent on R&D has halved roughly every 9 years since 1950

I think this should cause techno-optimists like Kurzweil pause. Yes, more money is being invested in healthcare than in any time period in human history, and yes, exponential economic growth and exponential technologies are allowing for this, but R&D costs are also increasing exponentially. The two factors are cancelling each other out, giving us sub-exponential improvement in health metrics. Therefore, I don’t expect life-expectancy to follow an exponential curve, unless some underlying dynamic changes which allows dramatically more resources to be allocated to tackling the problems of life extension, or a paradigm-changing technology leads to a new market dynamic. What we seem to be learning is that biology is very difficult once you’ve gotten past the low-hanging fruit.

What causes Moore’s law?

All of this really begs the question – what makes Moore’s law so perfectly exponential? Most accounts of Moore’s law are purely descriptive. There are a few popular notions floating around which propose a cause, however. One is that Moore’s law is a “self-fulfilling prophecy”. The semiconductor industry sets its targets by trying to beat the law, and invests whatever money is necessary to meet those targets, assuming that otherwise, inextricable market forces will leave them behind. In so doing, the industry makes sure to follow Moore’s law precisely on schedule. This explanation may explain why Moore’s law progresses with such regularity, but it doesn’t explain how executives have been able to continue the exponential progression without hitting a wall.

When trying to ferret out why Moore’s law has worked for so long, it is easy to get quickly lost in the weeds studying the numerous technological hurdles in silicon and VLSI technology that had to be overcome. I have neither the time nor expertise to follow such a route. Numerous challenging technological innovations, each seemingly not very important, have collectively allowed Moore’s law to continue. These developments have largely focused on the miniaturization of transistors. One reason for the focus on transistor size is that the cost of silicon wafer fabrication increases dramatically with the size of the wafer. Thus, it is hard to improve chips (at fixed cost!) by simply increasing their size – doing so means fewer chips per wafer and higher cost per chip. The key is being able to manufacturer more transistors in a smaller area. This requires more capital expenditure to develop and build more sophisticated lithographic equipment, but these one time costs can be recuperated from the ability to manufacture more chips per wafer. Another reason manufacturers seek to cram more transistors into a smaller and smaller area is that power consumption is proportional to chip area. Power consumption can only increase to a certain level, beyond which the chip melts down. Clock speed increases power consumption, so reductions in power consumption from a smaller area allow for increasing clock speed. Physics-based scaling arguments support a similar dynamic – smaller components can operate at higher frequencies.

Another factor behind Moore’s law is that better chips help facilitate the design of future chips. No human can lay out a chip with a billion transistors in an optimal manner – it must be done using very sophisticated design software, which requires sufficiently powerful computers to run. This dynamic was especially important during the early years of Moore’s law, as chip design transitioned from being done entirely by hand (lithographic plates were hand painted) to being automated by increasingly sophisticated software.

While the three factors I just mentioned (the self-fulfilling prophecy, silicon wafer economics, and computer-aided design) all played an important role in bringing about Moore’s law, I believe that underlying it all is a deep lesson about economics. Exponential trends usually end in an “S” curve not because of physical limitations, but due to economic ones. True physical limitations, such as the speed of light, are rarely reached before economic limitations stop progress. As was already mentioned, investments in manufacturing technology can reduce the price of goods. However, the amount of capital that needs to be invested increases rapidly as the easy efficiency improvements are solved and harder ones must be tackled.

In the case of semiconductor technology, this principle is called Rock’s law:

The cost of a semiconductor chip fabrication plant doubles every four years.

In the case of automobiles, the ‘easy’ cost-reducing technology was the assembly line, followed by more challenging things such as industrial robots. One is able to continue to invest in cost-reducing technology as long as yields (revenue) increases at the same rate as the expenditures pile up. At some point, however, the expected increase in revenue does not offset the resources required to further reduce cost. In the automotive industry, this happened when virtually everyone of driving age who wanted to buy a car was able to buy one. At the point when everyone already has a car, the only way to sell more cars is to wait for new people to enter the market or for the old cars to break down.

Insatiable demand for transistors

What’s interesting and unique about IT is that there is an insatiable market demand for it. People are willing to replace their current computers every few years for ones that are twice as fast at the same price, and in fact they have been doing so regularly for the past two decades. The ‘turn-over’ rate for PCs and smartphones during the past decade has been only a little longer than the doubling time of Moore’s law (~2-4 years). Moreover, people are constantly finding new applications for computers, and therefore, industries are buying more and more per worker. As the US economy becomes more based on information rather than manufacturing, IT becomes more and more important. Furthermore, the amount of “big data” that could be put to use seems to be unlimited. The larger data sets become, the more transistors are required to process them. There is also the trend of “software eating the world” – things traditionally done by humans are continually being replaced or augmented by increasingly sophisticated software.

Markets themselves are based on the flow of information in the form of prices. The price system efficiently conveys information about market conditions. As F.A. Hayek pointed out, the price system is essential – it conveys important information which cannot be gathered in any other way. Better IT tech leads to better information processing, which leads to more robust markets, which in turn leads to more wealth that can be invested back into IT technology. The insatiable demand of the market for more transistors is the underlying driver of Moore’s law.

Addendums:

I came across a recent interview with Peter Thiel were he directly acknowledges that he disagrees with many of the exponential projections Kurzweil gives in his book The Singularity is Near.

12-18-17 : in economics, one cause of the diminishing returns from investment of more resources is the so called “learning curve” effect. It may be worthwhile exploring the literature on learning curves (both in economics \& society ) and see if they have connections to Moore’s law vs traditional S-shaped development curves.