Why do we see the frequencies we do?

Why can’t we see in the infrared or ultraviolet?

The reason is that our eyes are the result of millions of years of evolution. Millions of years ago, our ancestors lived in the ocean, so they had to see through water. Water is mostly transparent to visible light, but absorbs most other forms of electromagnetic radiation rather strongly. Even when our ancestors started living on land, our eyes remained full of ‘vitreous humour’, which is mostly water. You can’t really appreciate how marvellously tuned our eyes are to seeing through water until you see the absorption data itself on a log-log plot, for instance as plotted in the famous textbook

Classical Electrodynamics by J.D. Jackson:

(http://www.moreisdifferent.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/jackson_water_spec.gif)The visible range is only a tiny part of the absorption spectrum, located between the two vertical dashed lines.

(http://www.moreisdifferent.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/jackson_water_spec.gif)The visible range is only a tiny part of the absorption spectrum, located between the two vertical dashed lines.

I believe some of the data Jackson shows comes from the master’s thesis of David J. Sigelstein, which is publicly available here. To create a plot like this took a lot of work – experimental data had to be collected from many different sources, since the frequency range of any given experimental setup ends up being rather limited. The lowest frequencies between 10^9 – 10^12 Hz are in the GHz-THz range and are measured using dielectric spectrometers. Even within this range, the range of each experimental apparatus is limited, so one has to link together experimental data from 2 – 3 different sources of experimental data. Likewise there are separate measurements for the infrared, visible and UV parts of the spectra.

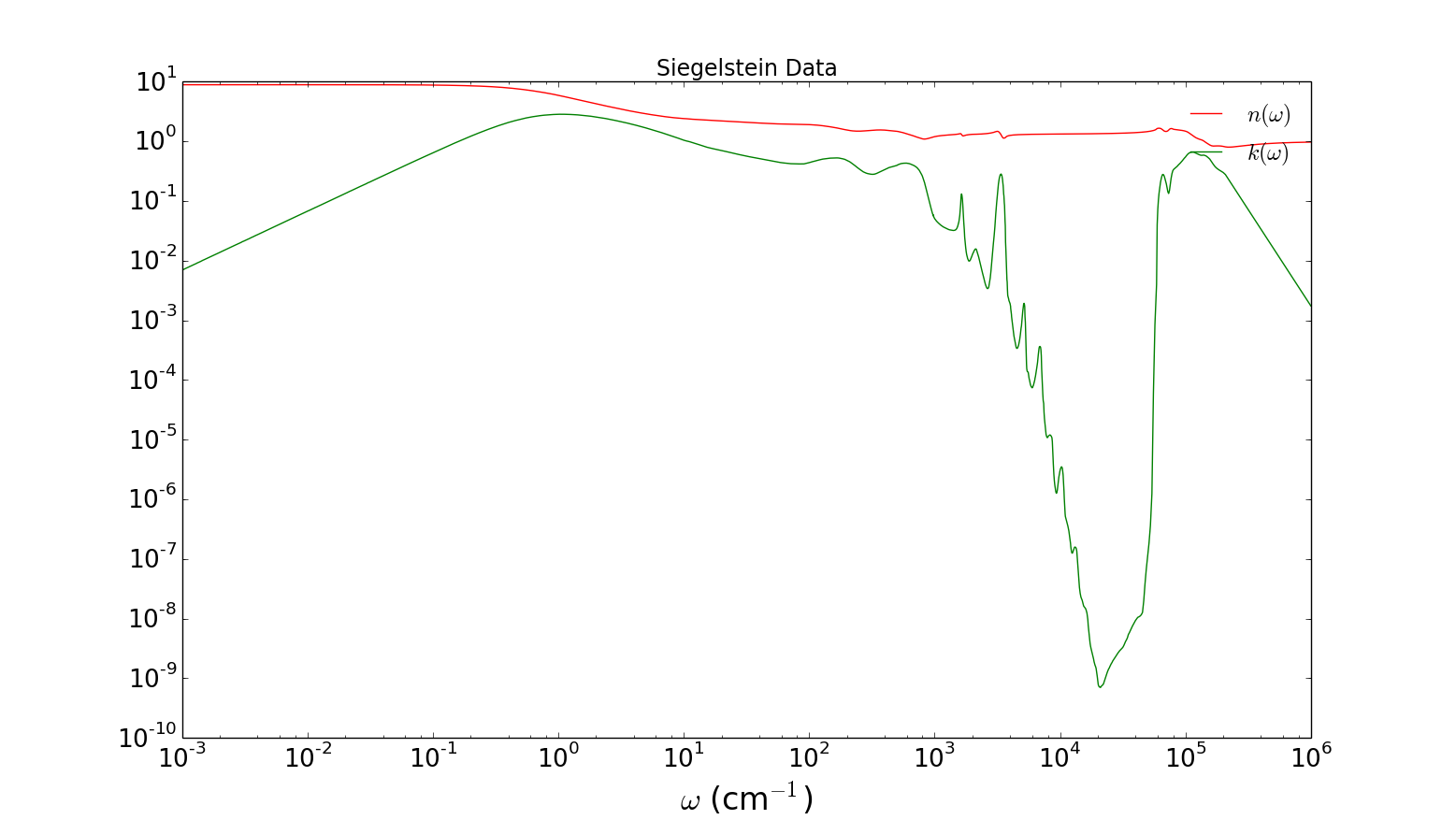

Here is my own plot of the data, plotted with the matplotlib Python library:

‘n’ is the index of refraction – it tells how much light is bent, and also how fast it travels in the water. ‘k’ is the absorption. (technical note – the ‘k’ I plot is the ‘extinction coefficient’, which is slightly different from the “infrared” or optical absorption coefficient (alpha) plotted in Jackson. The difference that only becomes really apparent at lower frequencies.)

Let me label all of those peaks. Each peak corresponds to a seperate absorption process in water. Here is a summary of the processes involved:

— .5 cm-1 – The “Debye” absorption due to collective polarization relaxation. Mircowaves use the big peak here to efficiently heat food.

— 1 – 100 cm-1 – H-bond network vibrational and relaxation modes (there are many)

— 200 cm-1 – H-bond stretching absorption

— ~600 cm-1 – Librational (rotational) absorption

— 1500 cm-1 Bending

— ~2000 cm-1 Bending + librational overtone

— ~3500 cm-1 Symetric & antisymetric stretching

— 4000 – 10,000 cm-1 lots of weak overtone peaks

— ~40,000 cm-1 the so-called “UV edge” – at this frequency, the radiation is high enough energy to ionize water – ie. to kick out electrons from the molecules. The absorption at frequencies above this edge is all is due to ionization processes and Compton scattering between light and electrons.

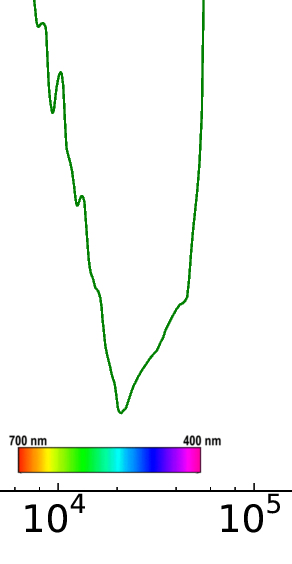

Besides seeing why we see in the visible, there is another neat thing you can observe in Jackson’s figure if you look closely – you can see why water is blue. Of course, everyone knows that water appears blue when it reflects the blue sky. Less people are aware of the fact that water has an intrinsically blue color. If you look very carefully at the Jackson figure, you will see that there is more absorption towards the lower frequency (red) end of the spectrum. Here is a “zoomed in” picture of what’s going on:

As you can see, there are several absorption peaks that overlap with the red, yellow and green parts of the visible spectrum. These overtones are quantum mechanical in nature and are described in a bit more detail here. Because blue is absorbed least and red is absorbed more, water appears blue. The effect is very subtle, however, because the absorption is extremely small (note the logarithmic scale). The effect can be observed by eye by taking a tube of water about a few meters long with clear windows on each end, and looking through it. Scuba divers are also aware of this phenomena – if you dive deep enough, the water will appear slightly blue-ish, even on a cloudy day when the sky is grey.