Explaining the uncertainty principle correctly

“I think I can safely say that nobody understands quantum mechanics.”

– Richard Feynman, in The Character of Physical Law (1965)

One of the greatest things about being a physics major is that you learn quantum theory and can proudly say that you understand it. When I say “understand” I mean that you are able to apply it to make predictions about reality. As Feynman rightly pointed out, nobody understands quantum mechanics in the sense of understanding why it is the way it is. Fortunately, we don’t have to understand why it is to know how to use it to make predictions. Using quantum mechanics we can in principle understand almost everything in the universe, in the sense of being able to predict things. In this respect, the theory of quantum mechanics is the highest pinnacle of human thought, since it subsumes almost all of reality into a theory based on just a few axioms and equations.

Quantum theory is a mathematical theory – you start with a system (for instance a hydogen atom, made of a proton and electron), you plug it into equations, and then you calculate things that can be observed (for instance, spectroscopic absorption lines). Quantum mechanics can also be used to predict rates of chemical reactions, and material properties such as electrical and thermal conductivity. It is essential for understanding how semiconductors, lasers, and superconductors work – the behaviour of such systems could not be predicted or described by any prior physics theory.

One of the issues with explaining quantum mechanics to the public is that considerable mathematical prerequisites are needed. Even with basic prerequisites in place (calculus and linear algebra) for me personally it wasn’t until I started my third semester of study that I really felt like I understood the “mechanics” of how the theory works. Its sort of like trying to understand how a car engine works – it takes some investment of time, and the more time you invest, the better you start to grasp the ‘mechanics’.

Quantum mechanics is harder to explain than classical mechanics because the mathematics of quantum mechanics isn’t easily mapped onto any classical phenomena that people are familiar with. The central object of quantum mechanics is the wavefunction, which is complex multivariate function that, when squared, produces a probability density function. There is no way of explaining a wavefunction in terms of classical, intuitive physics.

The Uncertainty Principle

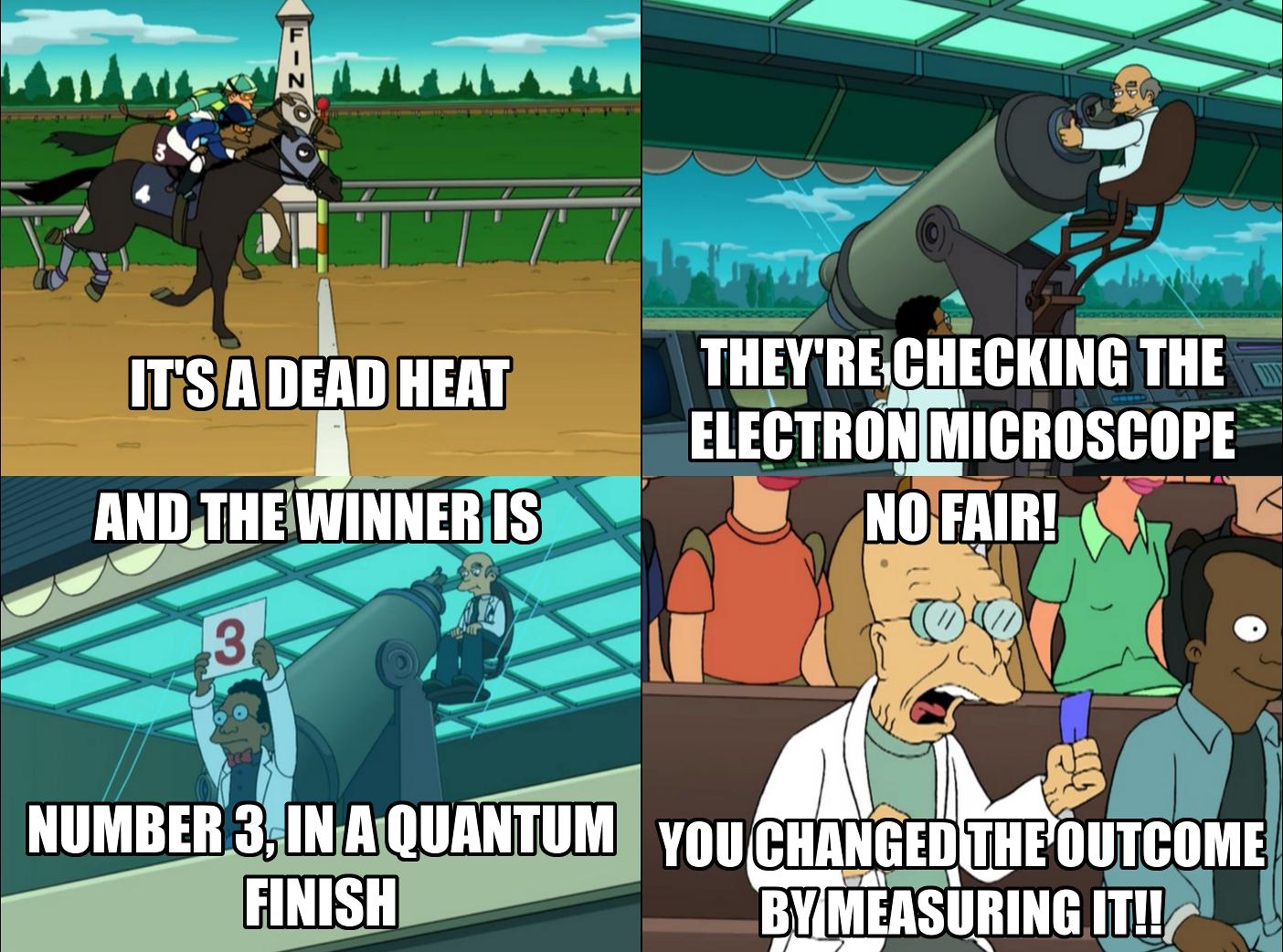

There are core features of quantum mechanics that can be explained accurately to anyone in a short amount of time, without any “dumbing down”. For instance, quantum mechanics says that we cannot know the both the position and momentum of a particle precisely at any moment in time. This is the famous Uncertainty Principle. Unfortunately, a lot of people go further and try to explain why the uncertainty principle exists by saying that measurements disturb the system. This is an incorrect explanation of why the uncertainty principle exists in quantum mechanics. The correct explanation is that it is intrinsic to the mathematics of the theory. There is no known reason why the uncertainty principle holds – it just does. Even if we had a measuring device which did not disturb the system at all, there would still be unavoidable uncertainty.

I believe the reason that this incorrect explanation is so prevalent is because during the formative years of quantum mechanics, Heisenberg introduced a thought experiment called the Heisenberg Microscope. A brilliant description of the Heisenberg microscope is given by A. Schiff in his book on Quantum Mechanics. Heisenberg imagined a very powerful microscope observing light being bounced off a particle, such as an atom or electron. Unfortunately, classical optics says that light cannot be focused perfectly by a lens – a lens’s ability to focus, or its resolution, is limited by the wavelength of light. By going to smaller wavelengths, you achieve greater resolution. However, light with smaller wavelengths causes more energy to be imparted to the particle. When the light bounced off the particle we can’t tell which way the particle travels because different scenarios of momentum transfer and recoil may be consistent with the observation. (the precise details get a bit complicated, but that is the basic idea).

A similar experiment holds for measuring momentum. Momentum can be measured by measuring the Doppler shift in the frequency of light being bounced off an atom. However, to measure frequency precisely requires shining light for a finite amount of time. During this time, the particle changes its position because of the light being bounced off it.

Unfortunately these thought experiments, while roughly true, are misleading, because they imply that the uncertainty in quantum mechanics is because of the act of measurement, when it is in fact intrinsic to the theory. In quantum mechanics, a situation where a particle has a precisely defined position and momentum is just impossible. It can never occur! This is part of the weirdness of quantum mechanics – we don’t know why the theory is like that — that’s just how it is!

But wait…

Those of you who are thinking deeply about this may wonder, though, how do we know that the uncertainty predicted by quantum mechanics isn’t just a trick caused by our measuring devices, and not actually something intrinsic to fundamental reality? Maybe particles really can have exactly defined positions and momentums, but because of unavoidable crudeness in measurement like what Heisenberg described, it appears that they don’t. In other words, how do we know that uncertainty is actually fundamental and not just a mirage caused by measurement? It turns out that we can make some measurements without disturbing a particle at all. A simple way is to shine particles (such as photons) through a slit and then measure whether they passed through with a detector. The slit works as a measuring device, telling us that photons were at a certain position a moment before they hit the detector. When photons pass through the slit, they don’t ‘interact’ with it – as far as the photon knows, the slit might as well not even be there! However, after passing through the slit, the photon’s momentum becomes undetermined, so after it passes through, we don’t know where it will hit the detector! This is the underlying basis for the classical idea of diffraction and part of the famous double slit experiment, which I am sure some of my readers are familiar with. Feynman thought carefully about how you might also measure the momentum imparted to the slit by the photon, assuming its momentum changes in a deterministic way. It turns out that if you try to measure how phonton’s momentum changes while passing through the slit, you can’t do it without loosing some accuracy in determining where the particle was when it was passing through!

Still not convinced? Some people have argued that there is a subtle hole in the above argument (I actually cannot remember the exact hole, but there is a subtle one). Proof of the intrinsic nature of uncertainty has been established in a variety of experiments, in particular an experiment called the Delayed Choice Quantum Eraser. I hope to explain this experiment in an upcoming post, but an explanation can be found as part of a Stony Brook physics lab.