Wasserfadden!

” Others say the earth rests on water. For this is the most ancient account, which they say was given by Thales the Milesian, that it stays in place by floating like a log or some other such thing … as though the same argument did not apply to the water supporting the earth as to the earth itself.””

- Aristotle, in On the Heavens (II,13,294a28) 350 BC

The wasserfadden, or water bridge, is a simple yet perplexing phenomena.

The wasserfadden was discovered by Lord Armstrong in 1893. In a speech to the Newcastle Literary and Philosophical Society, Armstrong described his experiment as follows:

“Amongst other experiments I hit upon a very remarkable one. Taking two wine-glasses filled to the brim with chemically pure water, I connected the two glasses by a cotton thread coiled up in one glass, and having its shorter end dipped into the other glass. On turning on the current, the coiled thread was rapidly drawn out of the glass containing it, and the whole thread deposited in the other, leaving, for a few seconds, a rope of water suspended between the lips of the two glasses. This effect I attributed at that time to the existence of two water currents flowing in opposite directions and representing opposite electric currents, of which the one flowed within the other and carried the cotton with it. It required the full power of the machine to produce this effect, but, unfortunately when it went to London, and was fitted up in the lecture-room, I could not get the full power on account of the difficulty of effecting as good insulation in a room as in the outside air. I therefore failed in getting this result, after announcing that I could do it, and I daresay I got the credit of romancing.”

Here is a nice video of the phenomena:

Here is another neat video with fluorescent tracer particles showing that, indeed, water is flowing from one beaker to the other:

Although the wasserfadden has been known about for 120 years, it is only in the last few years that it has been studied in detail. The first scientific paper on the wasserfadden experiment was published in 2006. It is important to note that similar phenomena, such as electrospraying, electrowetting and electrohydrodynamics were researched throughout the 20th century. The more recent study of the wasserfadden is an extension of such research and ties into previous findings and their associated industrial applications.

Among the papers on the wasserfadden have been a study of the heat and mass transfer , a study of the formation dynamics and a neutron diffraction study .

The obvious question surrounding the wasserfadden is how water is able to hold a shape despite the force of gravity. The explanation obviously hinges on the fact that water consists of polar molecules and is easily influenced by an electric field – a fact known since the 1800s. [ As a simple demonstration of this, a statically charged object (such as a rubber balloon) held next to a sink faucet will cause deflection of the stream of running water. ] This is often explained as being due to an alignment of the water molecules in the electric field. This is a rather poor explanation since it neglects the importance of water’s ubiquitous hydrogen bond network. Almost all water molecules participate in the hydrogen bond network, with an average of 3.5-3.75 hydrogen bonds per water molecule. The network is constantly in a state of flux, but individual water molecules are significantly constrained by it, at least for periods of a few picoseconds. Weakening a hydrogen bond requires fields on the order of 10^9 V / m while breaking a bond requires an even higher field. The electric field necessary to produce a Wasserfadden is by contrast around 10^6 V /m. Such electric fields may induce minor reorientation but are not capable of reorienting water molecules en-masse. Therefore it is more accurate to say that the electric field creates polarization by distorting or rearranging the hydrogen bond network, and not so much by pure rotation of individual molecules.

Several theories have been proposed over the years to explain the wasserfadden: (perhaps you already thought of one of these yourself) :

1 All of the water molecules partially align themselves in the electric field, transforming the liquid into a ferroelectric-like material which can (somehow) hold its shape.

2 Some of the water molecules form one dimensional ‘threads’ in the interior of the wasserfadden. A ‘tangle’ of these threads hold the rest of the water molecules in place.

3 The surface tension is greatly enhanced under an electric field, enough to support the weight of the water in the interior of the wasserfadden.

4 some combination of 2 and 3.

Recently the Wasserfadden was investigating using x-ray scattering using the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Lab. Two of the collaborators were Dr. Pariese, a Professor of Geology at Stony Brook University and Lawrie Skinner, who was a postdoc at Stony Brook’s Mineral Physics Institute from 2010-2013.

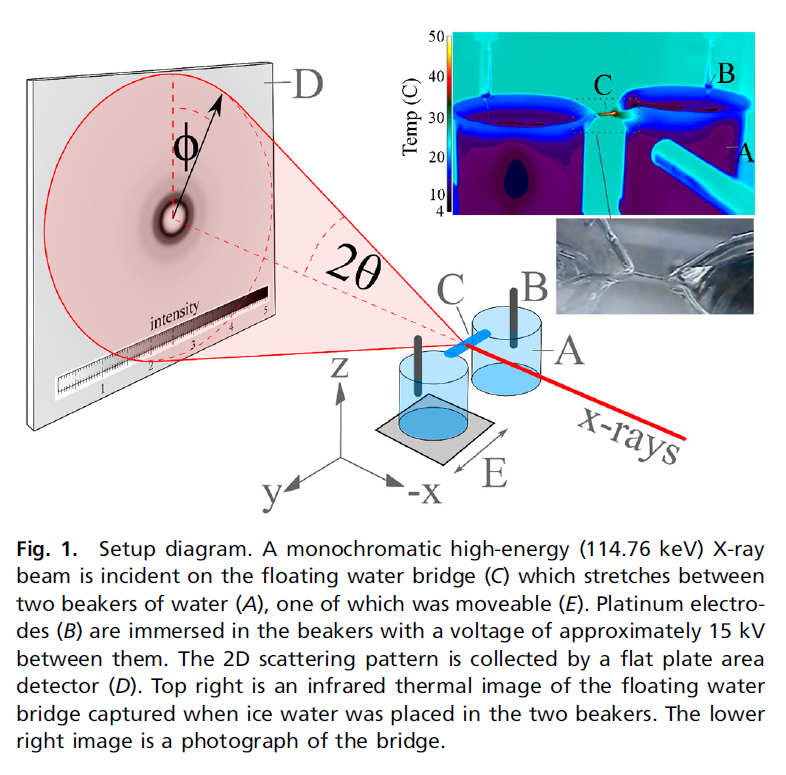

Here is a diagram of their setup, which is an example of a very elegant physics experiment:

From a careful analysis of the diffraction pattern the pair distribution function describing the local ordering of oxygen atoms can be derived. In particular, Skinner et al. went beyond the conventional analysis to search for any sign of directional anisotropy in the local ordering. To see exactly what the effect of electric field on the diffraction pattern might be, they performed molecular dynamics simulations with varying electric fields and calculated diffraction patterns from the simulation results.

From a careful analysis of the diffraction pattern the pair distribution function describing the local ordering of oxygen atoms can be derived. In particular, Skinner et al. went beyond the conventional analysis to search for any sign of directional anisotropy in the local ordering. To see exactly what the effect of electric field on the diffraction pattern might be, they performed molecular dynamics simulations with varying electric fields and calculated diffraction patterns from the simulation results.

The results clearly showed no anisotropy in the interior in the interior of the liquid. The conclusion is therefore that the water bridge is supported by enhanced surface tension.

What then, is happening at the surface? The surface structure and dynamics of water is very complex, involving an interplay of macroscopic and microscopic effects. In general, surface physics is much more difficult to study than the physics of the interior of things, which is called bulk physics. [The reason for this should be clear – the surface is a tiny volume, only a few atoms thick, while the bulk is huge. Because of this measuring what is going on at the surface without contamination of the signal from the bulk is very difficult.] As noted in the paper : ““The effect of electric fields on the surface tension of water has been notoriously difficult to study and the results have been inconclusive with no general agreement“”. Surface physics is not easy to study with a computer either (at least in the case of water), as the largest number of molecules amenable to (classical) simulation is at most 100,000, so one either ends up studying a nano-sized droplet or some other scenario which may not be simply relatable to the real world phenomena.

Therefore to get full understanding we will have to wait until someone has a brilliant insight into how to measure exactly what is going on at the surface.